This was born a simple idea: to tell a story. What it turned out to be is something different, something revealing the thousand faces of man, something that we were so eager to have our name on, but something that in the end, is simply unnamable.

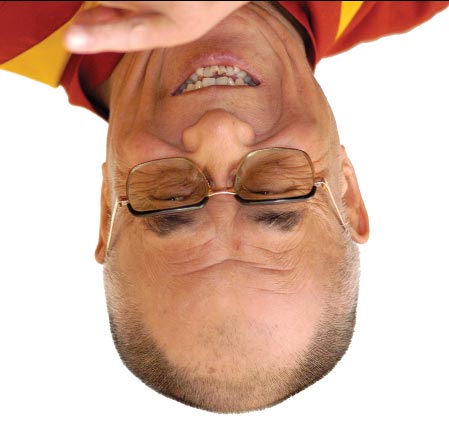

In an isolated downtown office a picture of a monk sits on top of a plain grey filling cabinet. Wearing the orange and red robes of monastic life, this exiled leader sits alone, arms tucked across his chest, legs jutting forward, toes pointing toward the network of overhead lighting, he's playfully rocking balanced on a standard office chair in the middle of a grand stage. Soon the black curtain separating him from everything else will open and he will address a Japanese theatre of thousands. His silhouette extends across the yellow cedar strips of the stage toward the viewer, not as a full shadow, but in a series of ripples, black waves of energy-in-wait captured by the camera.

The picture was taken by a swashbuckling ethnic Chinese nomad, personality part photographer, part card shark, part Zen monk. The swashbuckler's written several books (one with the monk in the photo), was one of the first people to cycle through the Himalayas, and has a rolodex that houses the names of business icons and heads of state: the kind of fellow who could tell you intimate secrets about the sacred sights of Lhasa during one phone call and convince you to cut a check for seven figures on another.

The son of a Hong Kong family caught in what he calls the inward-looking Chinese ghetto of the 50s and 60s, this sometimes shutterbug rebelled against the notion that expected him to be a 'good Hong Kong boy' and become an engineer or a doctor. Instead, influenced by the counter-cultural revolution of the West—beat writers and the Human Potential Movement—he left Hong Kong and met the world's most famous monk in an unusual tale of kidnapping and a beautiful girl. On an overland trip set to the backdrop of Afghanistan , Iraq , and Burma in the early 1970s, he figured a way to spend the rest of his life working as a part of an exclusive inner circle. From that inner circle he built the idea of a centre for peace and education called the DLC in Vancouver .

“Everybody is in business to an extent,” says this man who after all of his adventures finds himself DLC executive director, a position he calls a complex business endeavour. “By virtue of the fact that [the monk] is very involved with the DLC and he has very significant relations with powerful people around the world in places like Berlin, London, New York and Taipei it is natural that what we do in the center is tied to his friends in these places; [business] people who are very much concerned about making the world a better place. These are the type of people who will now come to Vancouver because of the DLC, people who might not otherwise have come.”

To support the DLC, the cyclist turned ED helped organized Connecting for Change, an exclusive closed-door workshop being conducted by three of the world's most recognizable business educators. Its purpose is to bring together both respected business and social leaders in small groups intermingled with oil and gas executives, non-profit entrepreneurs, pulp and paper CEOs, and environmentalists. Here they are to explore the interconnection between business and altruism looking for ways that the DLC can act as a global interaction point for the two traditionally opposed groups. Afterward they will discuss the possibilities in dialogue with the monk.

So is this simply a superficial love-in making business people feel better about themselves and the way they do and have done business? Hanging out with holy men is great for personal ego but what do business, profit, altruism and happiness really have to do with each other?

“I believe that the very purpose of life is to be happy,” says the monk at the center of the conversation. “From the very core of our being, we desire contentment. In my own limited experience I have found that the more we care for the happiness of others, the greater is our own sense of well-being. Cultivating a close, warm-hearted feeling for others automatically puts the mind at ease. It helps remove whatever fears or insecurities we may have and gives us the strength to cope with any obstacles we encounter. It is the principal source of success in life.”

Born June 6, 1935, this particular monk is the 14th in his line and said to be the living incarnation of Avalokiteshvara, or Chenrezig, the thousand-armed Buddhist Bodhisattva of compassion, who's vowed to liberate all living beings from suffering. He was revealed as the reincarnation of his predecessor through a series of tests ranging from specific questions to object recognition. Based on these tests—many of which are fantastic enough to sound fictionalized yet logical enough theories on energy to ring true—he was taken from his home at 9 years old and thrust under the tutelage of the most learned teachers of a 2500 year-old epistemology. He is a master of metaphysics, has collaborated on dozens of books on topics ranging from prayer to science and has spent a lifetime devoted to the alleviation of suffering through the perpetuation of compassion and happiness. As all Tibetan Buddhists do to some extent or another, he explores possibilities related to these subjects through a combination of experience, meditation, and strict logical analysis.

“Although Buddhism has come to evolve as a religion with a characteristic body of scriptures and rituals,” writes the monk. “Strictly speaking, in Buddhism scriptural authority cannot outweigh an understanding based on reason and experience.”

From his first book he also writes extensively about his strong distaste for politics, yet his office is rife with it and his central goal—to return to Tibet—is as high a profile political maelstrom as it gets.

A minister at the Chinese Embassy in Ottawa recently rebuked Canada's open support of the monk, suggesting such an open display of affection toward religion is likely to further hinder relations between the two countries and impede BC's Pacific gateway aspirations.

“He himself is not only a religious leader, he is doing some political activities abroad,” the minister tells a local newspaper. “So we hope that the Canadian side will take note of this and pay much more attention—greater attention—to this, and not to provide him with an arena to have political activities.”

Canada is already having open trade difficulties with China in vital areas of the country's economy, especially in acquiring Chinese approval as a preferred tourist destination. Without that stamp of approval Canada could stand to lose on hundreds of millions of dollars in tourism revenue generated by what the World Tourism Organization estimates is 31 million Chinese that travel abroad each year.

But it turns out there are actually more important things than attracting Chinese business. In fact, the pursuit of happiness might just be a perfect economic venture for Vancouver .

A BC-based director of the Business Development Bank of Canada and one of Canada 's most respected economists says that the one-of-a-kind DLC has the potential to attract many renowned academics and business leaders to Vancouver .

"The DLC will undoubtedly have a positive impact on the BC economy,” she says. “Mainly in the areas of education and spirituality."

For today that impact is palatable and I find myself looking down on some of the most powerful business people in the world, unlikely witness to an event that somehow definitively explain the all occurrences leading me to where I am right now.

The long musical echo of an ancient Hebrew shofar invites the monk to a circle of 16 chairs surrounded by four widening rings of 138 more. A small group of Coast Salish people led by a Grand Chief welcome him to their traditional land with song and drum. In the heartbeat of the drum, the protection of his hanging robes, surrounded by the ordered excitement of the leaders, the old monk is an orange and red moth wrapped by scores of circling swallows. An organizer comes to the front and presents him a small stone given to him by his daughter, with which he asks the monks to cast many ripples.

The monk, however, chooses not to let the reverence in the room last too long and is most at ease when the 15 other chairs forming this inner circle are filled with delegates, making him a part of, rather than the centre of the dialogue itself. In response to a question from the co-founder of the Environmental Children's Organization, about how business leaders and social leaders can create the will to engage with each other, he emphasizes that interdependence is more important now than ever before in human history.

“I think the business group and social sector, there is a connection,” he responds. “I think in the past maybe different sections can work more or less independent, OK. Now, today there is a new reality. All should work together, particularly businesspeople. Of course it's a very important part of society. Without money you can't do much. But that the business sector should concentrate only to make profit, it is not sufficient. [Business] should take responsibility for the society or the community, then satisfaction with their business improves and more profit, more respect.”

Religious or not, it's easy to see the monk is right. And as modest as he plays, many of his writings and teachings seem to hold the answers—or at least great insight—into man's most difficult and important question: how do we achieve true happiness? And that's something that has all kinds of people interested.

As the spiritual leader of Tibetan Buddhism—probably the most recognizable sect of the world's fourth largest religion—the monk has the ear of some of the most famous and powerful people in the world, he is practically the brand name for compassion and happiness as a result of his interactions with movie stars and musicians. Certainly there is no shortage of people lining up to cash in on the Nobel Peace Prize winner's reputation.

The fact is Buddhism generates billions of dollars in revenue from tourism, book sales, and donations each year. Monks in countries such as Taiwan, Thailand, Korea, and even China have to be as much MBA as they do Zen in order to manage the wealth generated by a revival in both their economies and Buddhist practice. Buddhists numbered 127 million in 1900 and 353 million in 2001 but that number is greatly altered by the inclusion (or exclusion) of China, where it is estimated that 33% of the population shares an affinity with the religion.

According to many of those in attendance, this peculiar meeting of monastic robes, bleeding hearts, and bullet-proof business suits may—for better or worse—permanently change the way the business world views British Columbia .

A Portland-based global general manager for Nike's women's line and one of the dialogue participants claims this growing sense of interconnectedness has the biggest businesses in the world—the ones who's logos have been juxtaposed with swastikas—changing the way they operate. She says Vancouver has a central role to play in that process as a result of the DLC.

“How you bridge the gap between the corporate world and the social sector is so important. It wants to happen. To create a venue where you can bring people together and have true dialogue is pretty significant. Right now, Vancouver is the centre of the radar.”

A DLC trustee likens the shift in business norms to the abolition of slavery. He says that businesses are learning that they don't just have to produce and sell products. Instead they have to find ways to do business that are both good for people and the planet, ways that they are at peace with as businesses and as individuals involved in those businesses.

“There is a growing sense among [business] people that their businesses ought to reflect human values and those values are undergoing significant change. Business people have to find the way to bring that awareness into practice. It's like the moral shift that happened quite quickly less than two centuries ago regarding slavery; it goes back to ‘Oh, that's wrong and this is right.' It is not just that I have to sell my cotton. It's that I have to find a way to get my cotton in a more humanly responsible way.”

The word ‘sustainability' seems to be the word capturing this intermingling of business and ethics. In fact, it's now almost a cliché—a feel-good tag trotted out to sell everything from automobiles to the Olympics. Still, the concept of sustainability seems rooted in the ascendance of so-called hippies into the highest ranks of authority in various sectors, including business. Their influence, combined with the rise in economic stature of their 30-something children, represents an empowered critical mass in society at large. But this isn't a critical mass of malcontents tearing down Nike signs or having pot-smoking sit-ins to protest the war. Instead, it's a group of educated, practical, ethically minded citizens who understand how the fates of business and society are intertwined. Together, they form a large, economically powerful portion of the consumer base that the business world can't afford to ignore, and one that may just be catching on to what the monk already knows

A Connecting for Change participant and banking CEO who admits he's a little sceptical of the monk says he never imagined today's discussion would be so relevant from a business perspective. He says the weekend reveals just how big a role Vancouver can play in helping the two sectors stand together. This interaction, he says, represents a significant shift in global business and a tremendous opportunity for the BC economy.

“I think the most striking thing about Vancouver is the number of business people and the number of non-profit organizations that are trying to talk to each other. [The monk] called the social sector and the business sector the sheep and the yak; at one time I saw you and you were a yak and I was a sheep and we didn't have anything in common. Now non-profits are learning how to borrow money and business people are learning how to use their skills to help them. I think ultimately the big power of the [DLC] is going to come from enlightened business and non-profits who aren't just tilting at windmills and bleeding hearts, but that understand how things are done, how the economy works.”

Several times in the book The Wisdom of Kindness the writer alludes to an over abundance of difficulties with electronic equipment and recording devices in the monk's presence. During the 3-day dialogue series leading to this session there were in fact many sound difficulties. Those charged with technical detail were scattered as white noise trying to figure the problems. The results made the monk's voice—a naturally deeper version of the up and down croakings of Star Wars' Yoda—sound in a thousand different tones. At one point he gaves a very mischievous grin and kind pat to the arm of the grip attending to adjustments to his mic. Now, however, his voice is clear and stresses the importance of interaction between individuals and the infinite reward that can result from open-mindedness.

“I feel the individual is very important, so looking after oneself is very justified,” says the monk. “But if you look more deeply, then one individual, no matter how able or strong, without society he or she cannot survive. So therefore, for one's own interest you have to think of other's welfare. When somebody is in difficulty, if I take the position that I am better, I have no such problem, it is much less effect than [helping them]. The image here is to try to stand up together so that when someone has fallen down you should also lay down and try and get up together.”

“Compassion is not a religious business,” says the monk, who outwardly wishes the DLC would simply be a center for peace and education without his name attached at all. “It is a human business. It's not a luxury. It's a necessity.”

Miguel Strother no longer writes for himself.

Photo Info:The Dalai Lama

Photo Credit: Taken from the Dalai Lama's official website without permission, though, the website says if you want to print it out for personal use, that's ok.

Published On: February 14, 2007

Permanent Location: http://www.forgetmagazine.com/070214c.htm